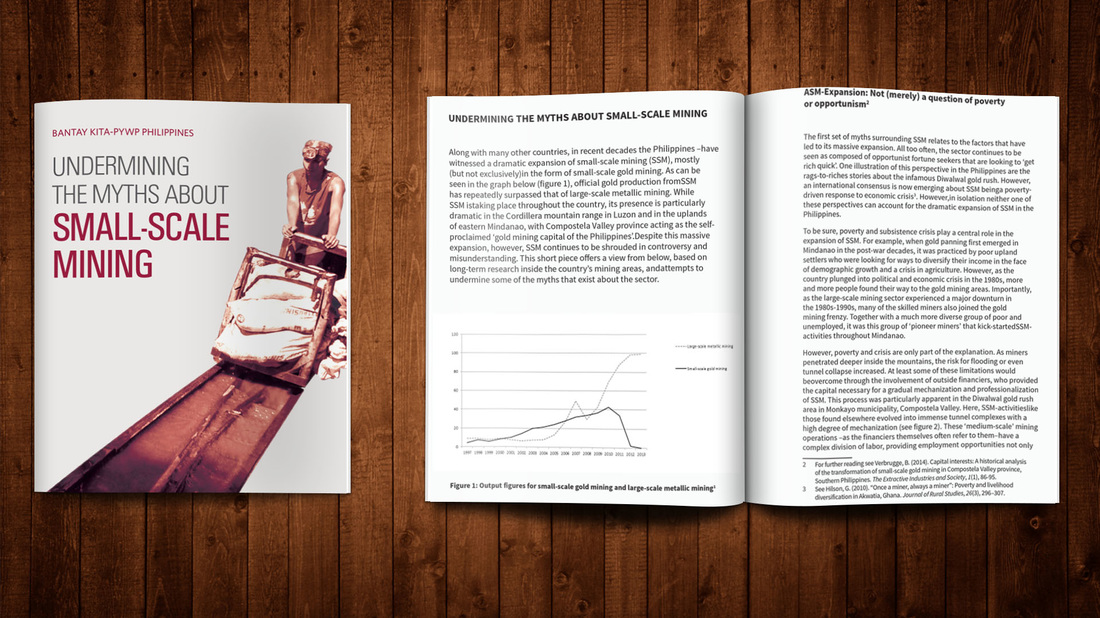

Excerpt:Along with many other countries, in recent decades the Philippines –have witnessed a dramatic expansion of small-scale mining (SSM), mostly (but not exclusively)in the form of small-scale gold mining. As can be seen in the graph, official gold production from SSM has repeatedly surpassed that of large-scale metallic mining. While SSM istaking place throughout the country, its presence is particularly dramatic in the Cordillera mountain range in Luzon and in the uplands of eastern Mindanao, with Compostela Valley province acting as the self-proclaimed ‘gold mining capital of the Philippines’. Despite this massive expansion, however, SSM continues to be shrouded in controversy and misunderstanding. This short piece offers a view from below, based on long-term research inside the country’s mining areas, and attempts to undermine some of the myths that exist about the sector. About the Authors:Dr. Boris Verbrugge has recently (May 2015) obtained his PhD from Ghent University, Belgium. He is currently a post-doctoral researcher and lecturer at Radboud University, Netherlands. His research deals with small-scale gold mining in the Philippines, particularly in eastern Mindanao. In total, he spent 10 months of field research in the Philippines, including in Compostela Valley province, Benguet, Agusan del Norte, South Cotabato, and North Cotabato. Throughout this research, Boris has interviewed over 175 people, including small-scale miners, government officials, local politicians, local landowners, mining financiers, NGO workers, and academics. Throughout, he was assisted by different NGOs, research institutes (including AFRIM, the Alternate Forum for Research in Mindanao), and Bantay Kita. Ms. Beverly “Bon” Besmanos is taking her Masters Degree in Anthropology at the Ateneo de Davao University, Philippines. She works with Bantay Kita-Publish What You Pay-Philippines as Subnational Coordinator for MIndanao. Bon was formerly employed by the Alternate Forum for Research in Mindanao. Her vast work experience with communities, local and national governments, and industry hasgiven her an exceptional understanding of mine-related regulations, policies, and programs, and the challenges of implementation on the ground. Ms. Besmanos has conducted research for several mining-related studies, including this one. Content:

Content

Excerpt:This article considers the legal framework necessary to support this system of monitoring. It first examines whether existing Philippine laws are sufficient to compel mining contractors to be transparent in all stages of the extraction process. By identifying gaps in mining and mining-related laws, it will then provide recommendations on how to promote transparency. About the Author:Atty. Marie Gay Alessandra V. Ordenes earned her law degree and Bachelor of Arts degree (major in political science) from the University of the Philippines Diliman. She was a litigation lawyer before joining the government as a court attorney. She is currently Regional Director to Southeast Asia and Asia Pacific at the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative Secretariat. Content:

Excerpt:The idea of a President exercising emergency powers brings horrible memories in the Philippines. Emergency power is associated with the brutal martial law regime of the late dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos which lasted for more than a decade. In truth, Marcos did not have a monopoly on the exercise of emergency powers. Since the adoption of the 1935 Constitution, Presidents have been given emergency powers for a variety of reasons.4 Not too long ago, President Fidel V. Ramos was granted emergency powers to deal with the power crisis in the 1990s.5 President Estrada mobilized the Philippine Marines to deal with the rising criminal activities during his term.6 President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo issued Proclamation No. 1959 declaring martial law in President in the Province of Maguindanao in response to the Maguindanao massacre. About the Author:Atty. Dante Gatmaytan is a Professor in the UP College of Law where he teaches Constitutional Law, Legal Method, and Local Government Law. Before he entered the academe in 1998, he practiced law through public interest law offices working with rural poor communities involved in environment and natural resources law, indigenous people's rights, agrarian reform, and local governance. He graduated with a Bachelor's Degree from Ateneo de Manila (B.S. Legal Management) in 1987 and a law degree (LLB) from the University of the Philippines in 1991. He holds Masters Degrees from Vermont Law School (cum laude) and the University of California, Los Angeles. Content:

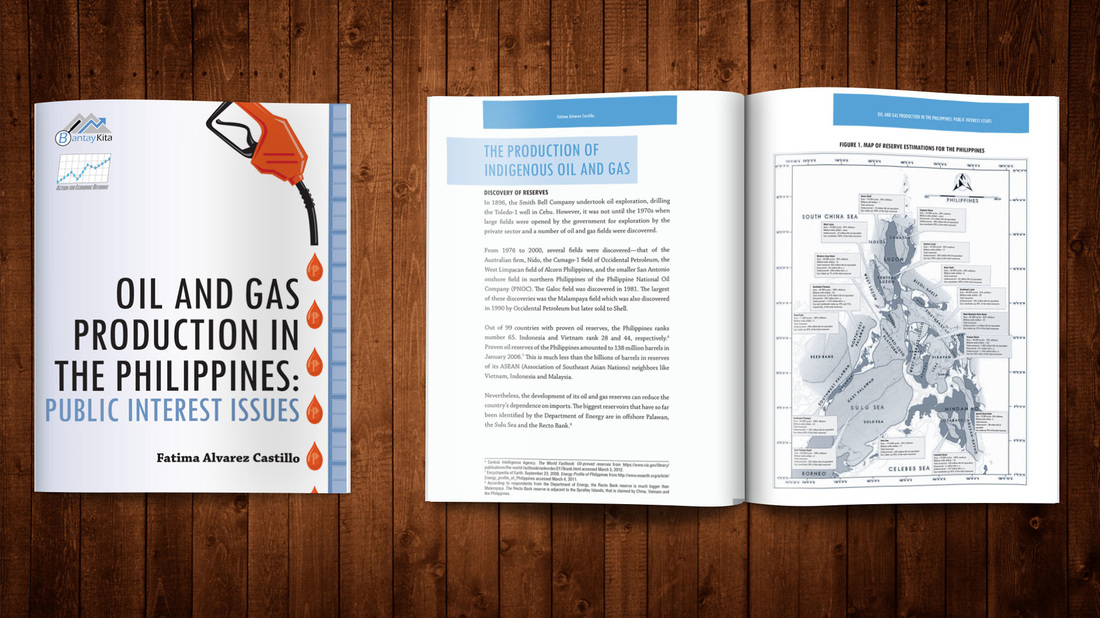

Excerpt:This paper is a scoping of public interest issues in Philippine oil and gas production. It is a preliminary examination of these issues for the use of Bantay Kita and other civil society organizations concerned with the extractive industries. The scoping was instructed by primary data from interviews with key informants and secondary data—from relevant laws, reports from the Department of Energy (DOE), and other documents and literature. About the Author:Fatima Alvarez Castillo is a UP Centennial and Full Professor of Political Science at the College of Arts & Sciences, University of the Philippines Manila. Content:

Excerpt:About the Author:Content:

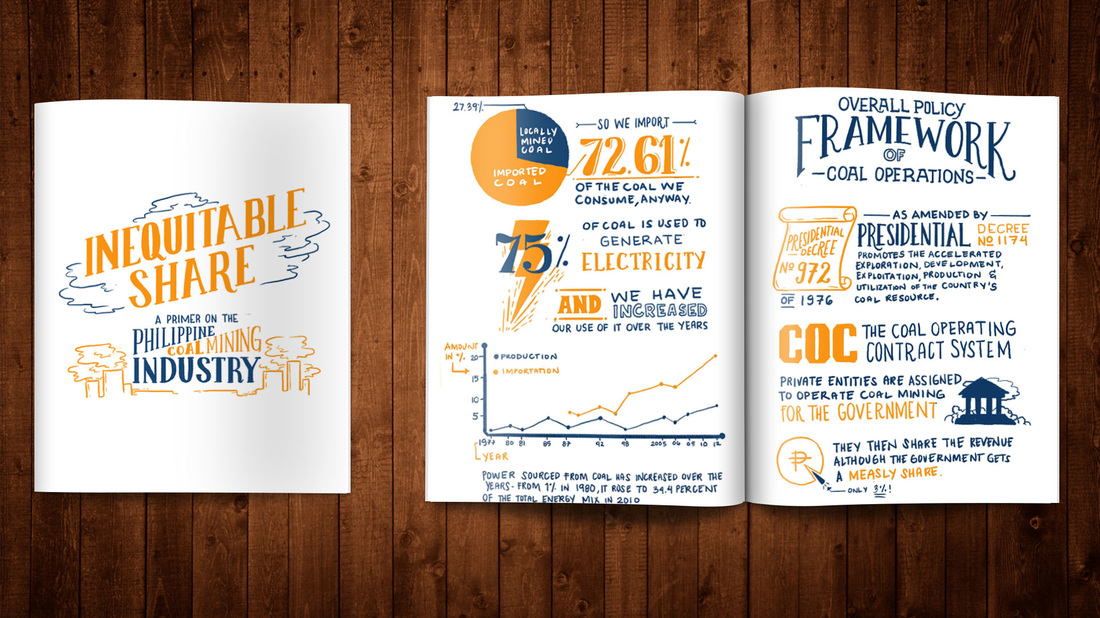

Excerpt:Coal is an important resource and serves as one of the most significant energy sources of the Philippines. With the country possessing a vast amount of untapped coal reserves, coal can help address the increasing demand for electricity in the country. As an industry, coal production also can also contribute to the growth of the national economy and expedite the development of local host communities. The use and production of coal, however, has generated concerns, especially and most commonly those relating to the environment and to public health. Harnessing coal’s potential therefore requires achieving a careful balance between the possible costs and benefits of coal production. The coal mining operators, the Philippine government, and the civil society play key roles in attaining the said goal. Nevertheless, these players and stakeholders are limited by the regulatory framework defined by the existing policies governing the industry. In order for each stakeholder to act towards an optimal and equitable outcome, the regulatory environment must be shaped and re-shaped to be made conducive in the attainment of the said objective. This paper analyses the Philippine coal industry, focusing on the coal mining operations in the country. It provides an overview of the Philippine coal market, as well as the regulatory framework in which the industry operates. The paper offers general analysis and broad discussion of several regulatory concerns (e.g. revenue-sharing, environmental regulation, and social development) which call for further scrutiny and public attention. About the Author:Anton Miguel Ragos is a researcher from Action for Economic Reforms, a non-government organization conducting policy analysis and advocacy on key issues of economic reforms and access to information policies. He has written on various fiscal policy issues, particularly on tax policy reforms. He is currently an MA Economics student at the UP School of Economics. Content:

Excerpt:The EITI workshop participants were very open to the information about EITI. Valid concerns were raised on the scope of the EITI, the composition of the Board, the implementation of EITI at the subnational level, the value of EITI to communities and access to information. Content:

Excerpt:After overthrowing the dictatorship of Ferdinand E. Marcos, Filipinos rewrote the fundamental law of the country. This time they wrote provisions that strengthened their position against the government. The strengthened their rights and put many safeguards against the abuse of power. They also directed Congress to write a Local Government Code that mandated their participation at levels that were unheard of in the country’s history. Today, the Local Government Code contains many provisions that reshaped the landscape for the extractive industry. Mining companies can no longer operate without first securing the consent of the local legislative councils. The State must first conduct consultations with various stakeholders before they can implement their projects. Local governments now legislate to protect the welfare of their constituents. This new legal framework has made things harder for the mining industry. In the past few years the national government has tried to circumvent these strictures in their behalf. President Benigno Aquino III issued Executive Order No. 79 essentially demanding that local governments agree with all his decisions. Issuances from the Department of Justice and the Department of Interior and Local Governments threaten local officials with administrative sanctions. About the Author:Atty. Dante Gatmaytan is a Professor in the UP College of Law where he teaches Constitutional Law, Legal Method, and Local Government Law. Before he entered the academe in 1998, he practiced law through public interest law offices working with rural poor communities involved in environment and natural resources law, indigenous people's rights, agrarian reform, and local governance. He graduated with a Bachelor's Degree from Ateneo de Manila (B.S. Legal Management) in 1987 and a law degree (LLB) from the University of the Philippines in 1991. He holds Masters Degrees from Vermont Law School (cum laude) and the University of California, Los Angeles. Content:

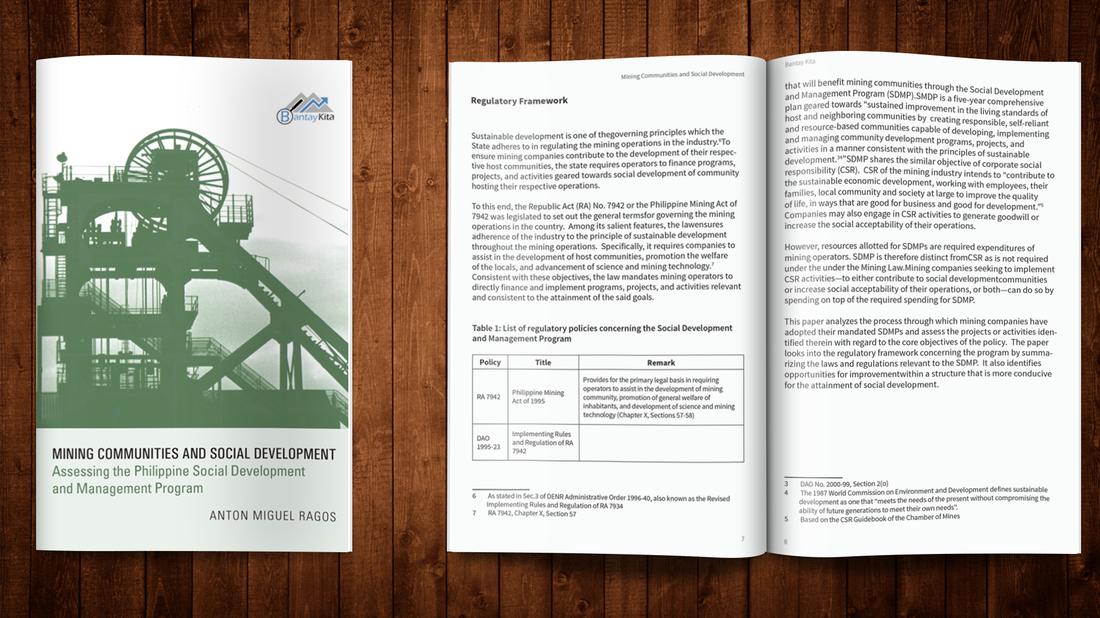

Excerpt:Currently, the state mandates mining operators to actively take part in the development of their respective host communities. Mining operators in the country are required to directly spend for and implement programs that will benefit mining communities through the Social Development and Management Program (SDMP).SMDP is a five-year comprehensive plan geared towards “sustained improvement in the living standards of host and neighboring communities by creating responsible, self-reliant and resource-based communities capable of developing, implementing and managing community development programs, projects, and activities in a manner consistent with the principles of sustainable development.34”SDMP shares the similar objective of corporate social responsibility (CSR). CSR of the mining industry intends to “contribute to the sustainable economic development, working with employees, their families, local community and society at large to improve the quality of life, in ways that are good for business and good for development.” Companies may also engage in CSR activities to generate goodwill or increase the social acceptability of their operations. About the author:Anton Miguel Ragos is a researcher from Action for Economic Reforms, a non-government organization conducting policy analysis and advocacy on key issues of economic reforms and access to information policies. He has written on various fiscal policy issues, particularly on tax policy reforms. He is currently an MA Economics student at the UP School of Economics. Contents

Type

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

What We Do |

Know More |

About Us |

Contact Us

[email protected] | +(63) 917 5105 879 1402 West Trade Building, West Avenue, Brgy. Phil-Am, Quezon City, Philippines |